The human immune system is amazing and incredibly complex. In fact, it’s one of the most intricate things I’ve ever had to learn. Effectively, you have your own personal army inside your body that relies on teams of specialized cells and communication networks between them. Just as tanks do a very different job than helicopters, your immune system has lots of weapons to bring to the fight. Every cell in your body has a name tag and cells in your immune system are constantly checking to make sure that only cells with the right name tag are there and removes anything with the wrong name tag. It can also learn about invaders it has seen before and prepare to recognize and defeat invaders the next time they’re encountered.

When a virus like COVID-19 comes into your body, it has an envelope surrounding with spikes coming out of it. These spike proteins serve as keys that are searching for a lock and the locks are found on the cells of your respiratory tract. In immunology we call these locks “receptors.” These locks have an important purpose in the body and they aren’t designed for viruses to enter, but viruses have evolved to take advantage of the locks that are available, even if they’re intended for other things.

One of the tools of the immune system that involves both weaponry and memory is the production of antibodies. Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins that your immune system generates in response to infection. There are two “invader” binding sites at the top tips of the Y. In the context of viruses, antibodies are what you want in order to protect you. But just like you need to have the right key for the right lock, you need to have the right antibody for the right virus. Since none of us had seen COVID-19 before when this pandemic began, nobody was producing the right antibodies. When the right antibody is present it can cover up the keys on the outside of the virus particle, getting in the way so that the key can’t enter the lock. If the key can’t enter the lock, then the virus never gets inside the cell and you never get sick. Antibodies can be made in response to natural infection or immunization.

So far, at least 15.8 million Americans have had the chance to make antibodies, or about 4.8% of the US population. That’s probably a low-end estimate, since we know that an estimated 40% of infected individuals never have symptoms and likely never seek a test. Disease underreporting is not uncommon in public health and that’s certainly true for COVID-19 too. But even if we assume that an additional 40% of what we have identified has been infected, then we’re still talking about only 6.7% of the US population. We’re still a long way off from herd immunity. The folks who have been infected already have presumably generated antibodies the old fashioned way. However, we don’t have data yet on how long that immunity lasts. In any case, that potential immunity that has already been achieved was not without cost. More than 290,000 Americans weren’t lucky enough to survive infection and countless others may have antibodies, but at the cost of cognitive dysfunction, permanent lung damage, strokes, etc. This is the advantage that a vaccine offers – the opportunity to gain immunity without suffering the ravages of this infection. We’ll talk about how the vaccine works next time. But when we expect that it will take 70% or more of our population to be immune in order to achieve herd immunity, then the vaccine is the way to accomplish that without hundreds of thousands of additional deaths. It is the path back to life that feels more normal.

On average, it takes about 7-10 days to start producing antibodies against an infection and you reach maximum production about 3 weeks after exposure (this is called the primary response). The next time you see the invader, your antibody response is both faster and bigger in order to protect you and this bigger and faster thing happens with each subsequent exposure (this is why booster shots work). This bigger and faster thing is called your secondary response. We don’t yet know how long natural immunity (through infection) lasts or how long immunity provided by the vaccine will last. It’s possible that boosters may be needed in the future.

Vaccines can make an enormous difference on suffering and death from a disease. The graph below shows how significant of a burden that pertussis (also known as Whooping Cough) used to be in the United States, by measuring cases reported each year. The first pertussis vaccine (called DTP, providing protection against a combination of diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis) was first introduced in the late 1940s. Prior to vaccination, the disease caused more than 250,000 cases in one year (around 1935). When DTP was introduced it took about 20 years but cases gradually declined to virtually nothing. It’s a reminder to us that the COVID-19 vaccines aren’t going to solve our problems overnight. But we can eventually get to a much better place, with more of us making it to a time when COVID-19 no longer impacts day to day live.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6702a1.htm

There’s a lot more to immunology than just antibodies, and even producing antibodies requires the coordination of lots of different cells and processes. But antibodies are the superheroes of your body’s fight against COVID-19 so I wanted to explain a bit about how they work. Next time we’ll talk about what’s unique about the RNA vaccines that are leading the development pipeline for COVID-19.

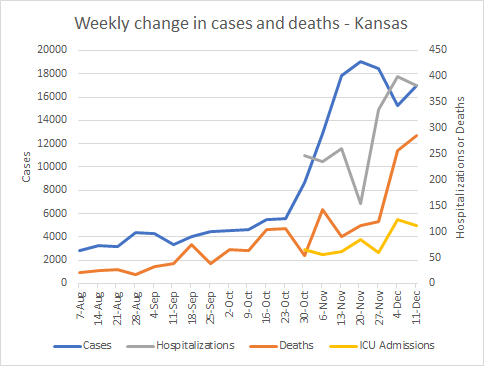

As we transition into a week-in-review analysis of Kansas, here is a graph that summarizes everything I’m about to show you. Cases (blue line) correspond to the left y-axis and everything else corresponds to the right y-axis.

Cases bounced back up slightly after a decline last week. Hospitalizations (gray) declined slightly as did ICU admissions. That’s certainly welcome news. Deaths continue to trend upward, however their rate of increase is smaller than the previous week. So let’s take the good news anywhere we can.

Testing

Testing remains weird ever since the Thanksgiving holiday. This most recent week we didn’t see the typical pattern we had observed during the week days. Testing seems to be decreasing overall - the opposite thing we want to see when our percent positive rate is as high as it is.

Despite the decrease in overall test output, our percent positive has declined over the past week.

Cases

This week there were 16,999 COVID-19 cases, an increase of 11.3% compared to the previous week. Here’s how those new cases were distributed across age groups, with the most recent week in the maroon color.

We can see that most ae groups are seeing new cases decline overall, but that’s not the case for those 0-9 and 85+ for whom cases remain high. We are also seeing some resurgence in cases across every age group (some smaller than others). This was the week that we expected to see the initial bump from Thanksgiving gatherings and so far it is here, but maybe not as bad as we were expecting. Then again, with testing output decreasing, it’s possible we aren’t identifying all the cases that are out there either.

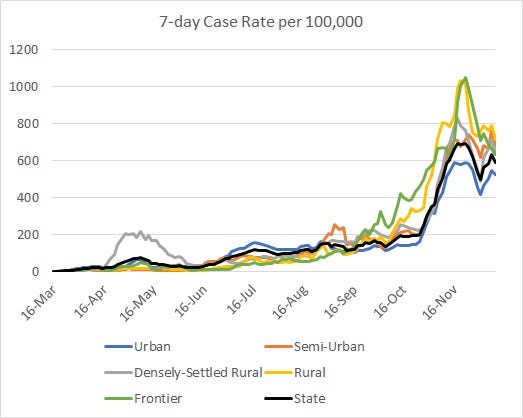

The next graph shows how case rates per 100,000 residents have varied over time for each county type in Kansas. You can check to see how your county is classified here.

Urban counties are faring the best in the fall/winter wave for Kansas and that’s interesting given their population density. However, urban counties were among those to enact mask mandates and perhaps that explains their lower case rates. There are also more opportunities to successfully adhere to public health guidance in larger cities, where grocery pickup and delivery, restaurant takeout, etc, is more available.

The next graph shows where outbreak (or cluster) associated cases have been distributed over the past 6 weeks (most recent week in green). We can see that long term care facilities (LTCFs) continue to be a big source of outbreak cases. Over time, we’ve also seen significant clusters associated with corrections, college/university, private business and schools.

Hospitalizations

This week Kansas recorded 383 new hospital admissions, a decrease of -4% compared to the previous week. The graph below shows how they were distributed by age groups over the past 8 weeks. The most recent week is the maroon bar, for each age group.

Hospital admissions increased for all age groups except those 45-54, 65-74 and 85+. However, hospital admissions remain very high for those 65+. It’s concerning to see the increases among children. Typically cases are mild for children and it might be easier for people to shrug off a case increase in this population. However, seeing that cases are increasing among kids and that enough of the cases are serious enough to require a hospital admission is a different thing entirely.

Overall, the number of patients admitted for COVID-19 over time seems to have plateaued. That’s certainly welcome news for now. But the worry is that with cases increasing again, will we see hospital admissions bounce back up too?

Deaths

There were 286 newly reported deaths this week from COVID-19 in Kansas, an increase of 11% over the previous week. The graph below shows how those newly reported deaths were distributed across age groups, with the most recent week in maroon.

Increases were noted for those 45+ with the exception of those 55-64.

The next graph shows how the death rate per 100,000 has varied over time for the different county types in Kansas. The state death rate (black line) continues to trend upward, with rural counties disproportionately impacted compared to other county types. Urban counties and densely-settled rural counties have the lowest death rates, through their rates are higher than we saw in the summer.

That’s it for this week. Please make good choices!

References

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/rr/rr6702a1.htm

https://www.coronavirus.kdheks.gov/160/COVID-19-in-Kansas

Kansas COVID-19 Updates is a free newsletter that depends on reader support. If you wish to subscribe please click the link below. There are free and paid options available.

My Ph.D. is in Medical Microbiology and Immunology. I've worked at places like Creighton University, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and Mercer University School of Medicine. All thoughts are my professional opinion and should not be considered medical advice.